Kent Kennan: Composer and Dear Friend

Funny how old memories creep up on one. While practicing on the Steinway piano at work the other day, and — between wrestling with a passage on a new work of mine and attempting to sort out a particularly tricky passage in a Beethoven Sonata (Op. 49) — my head was suddenly filled with thoughts of a friend of mine I’ve not spoken with for nearly two decades.

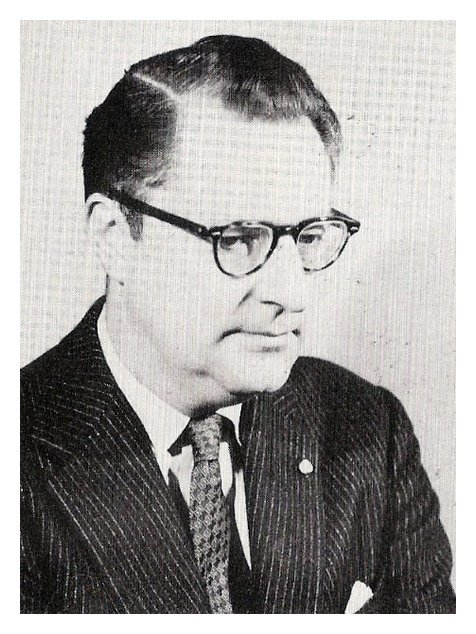

Kent Kennan

Kent Kennan was an American composer, author, and educator whose name was first brought to my attention around the time of my junior recital from my undergraduate years. The program was split between myself (playing lute transcriptions by John Dowland and classical guitar works of Heitor Villa Lobos and Leo Brouwer) and my good pianist friend Anne-Louise Hart. Among the pieces on Anne-Louise’s half was a Kent Kennan work called Retrospectives. More familiar with his books on music than I was with his actual compositions (his texts are still widely used in music schools today), I was immediately drawn in by this unique harmonic language, and resolved to dig a little deeper into Kennan’s music.

I’d lost track of that particular memory by the time I began my Masters’ studies at University of Texas at Austin, though it was abruptly brought back to mind when I became the recipient of the Kent Kennan Scholarship. At this point, Kent was a professor emeritus and no longer actively teaching at UT, though I was provided a mailing address where I might send a thank you note. I then had the opportunity to meet him a short time later at a UT New Music Ensemble concert (for which I served three-plus years as assistant conductor), and we would continue to bump into one another at various contemporary music events.

Toward the end of my graduate studies, I was hired as Director of Music at First Unitarian Universalist Church of Austin, which — as it turns out — counted Kent and a number of UT music professors among its founding members. From this point in time, Kent and I saw each other with greater frequency and developed a proper friendship. Desiring to push the institution’s high-quality — but very traditional — music program in a more adventurous direction, I began programming works by contemporary composers, including those written by Kent. To my thinking, anyone wishing to attack my new music leanings (or which there were more than a few) might be less inclined to do so if a regularly featured composer was sitting within earshot.

When I say Kent and I were friends, it should be stated that there wasn’t remotely a sense of equality. I was at the start of my career, while he was a Prix de Rome-winning composer whose works had been performed by many of the world’s major orchestras. Not one to embrace social niceties, he could be pretty gruff toward those performing his music (I once had a pair of friends play his famous Night Soliloquy — this version being the transcription for flute and guitar — and when Kent came up in the greeting line afterward, his solitary comment was “you’ve got a wrong note on the second page”). Another time I’d programmed a rock piece, which prompted a Monday morning phone call (basic gist: he wasn’t impressed) in which he quoted — no joke — his own orchestration book at me (something centering on how the snare drum should remain confined to evocations of militaristic moods) We ended the call agreeing to (strongly) disagree, but we, we nevertheless grew closer as time went on. I’d sometimes join him for lunch at his retirement community, where he’d regale me with tales of his compositional travels, hanging out with his good friend Samuel Barber, and discuss politics (in which he was deeply knowledgeable: his brother was famed diplomat and historian George F. Kennan, after all).

Kent’s brother, George F. Kennan

Sometime in the third year of my directorship, I decided to program his unpublished work “A John Donne Prayer” for chorus, piano, and glockenspiel. Thus far I had programmed others to perform his work, so — as conductor — this would be my first time to be on the firing line should the performance go south. With this firmly in mind, I studied the score with vigor and rehearsed the singers mercilessly. I dropped by his place to ask questions about the score, tempo variations, and anything I could think of to ensure that — at the very least — he’d not completely hate the performance.

When the day of the performance arrived, I was nervous, but more prepared than I’d been for almost any other piece I’d directed. I’d worked with some of the biggest composers in the field, but none of them I’d have to see on a weekly basis if they weren’t pleased with my talents. I felt the group performed went quite well, but — knowing Kent’s infamous pickiness — I braced myself upon the composer’s approach. The perma-gruff expression was there, but then he stopped, melted into a smile, shook my hand, and said “that was really quite excellent… thank you, Brent!”

As one who has built a career and reputation for not always giving a flying you-know-what about other people’s opinions, I’ll confess: I giddily walked on air for the rest of the day.

And the next day as well: it turns out that Kent had rung up my office phone and left a short-but-effusive message, thanking me once again for the good work. I saved the voicemail, and would sometimes play it for myself whenever I needed an emotional pick-me-up. I continued this practice even after he passed away the following year… perhaps even more so. I still kick myself for forgetting to record it on to an external device before the office switched voicemail services several years later, erasing all of my saved messages. Sigh… I had listened to it so much I could probably recite it verbatim, but I mourned the loss of this one, final memory of his voice nearly as much as I mourned his death.

Which would have made for a bittersweet end to this tale, but it’s not quite through.

Shortly after Kent’s passing, a mutual friend — acting as his executor — called me up and said he had two things from Kent for me. One was his beloved navy blue sweater he had worn for many of our meet-ups, which I still own to this day. The other was his piano… the same one at which he and I sat playing through scores at his apartment, and which is now the very Steinway upon which so many concerts and services are still played. The very one with which I’ve spent countless composition, recording, and practicing hours over the past couple decades.

The memory flash from two days back must have served to remind me that it has been nineteen years to the day that Kent left us. Or perhaps his ghost was passing through to whisper that' I’d gotten a couple notes wrong on page two of my Beethoven sonata…

Here’s to you, Kent Kennan. Thank you for your mentorship, friendship, and music.