Ralph Vaughan Williams at 150

“Who you calling ‘genteel’?”

There is a rather sizable list of composers I’ve long liked, but couldn’t quite love. More often than not, this was due to a perceived lack of “edge” in my mind.

Bach, Beethoven, Rorem, and so many more lived here for ages. Then one day, something clicked in my head upon hearing something pushing the edge (for the aforementioned cats, this would be Crucifixus from B-Minor Mass, Gross Fuge, and Pilgrim Strangers, respectively), thus carving out a warm spot in my heart. Even to contemporary ears, the deeply felt dissonances therein can cause your average symphony subscriber to squirm uncomfortably in their seat (to which I say: more please).

As a conductor, I’ve had the pleasure of waving a baton at a great many of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ works, including Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, Five Mystical Songs (more times than I can count), Serenade to Music, Fantasia on Greensleeves, and more. His craft and musical imagination cannot be denied, and I’ve always enjoyed the beauty of his writing whenever I’ve engaged with it as a performer. As a listener, however, so much of his output hit me as just a bit too genteel, too nice, to proper… and too sappily programed to yank at the heartstrings (and to loosen the pursestrings of donors, of course).

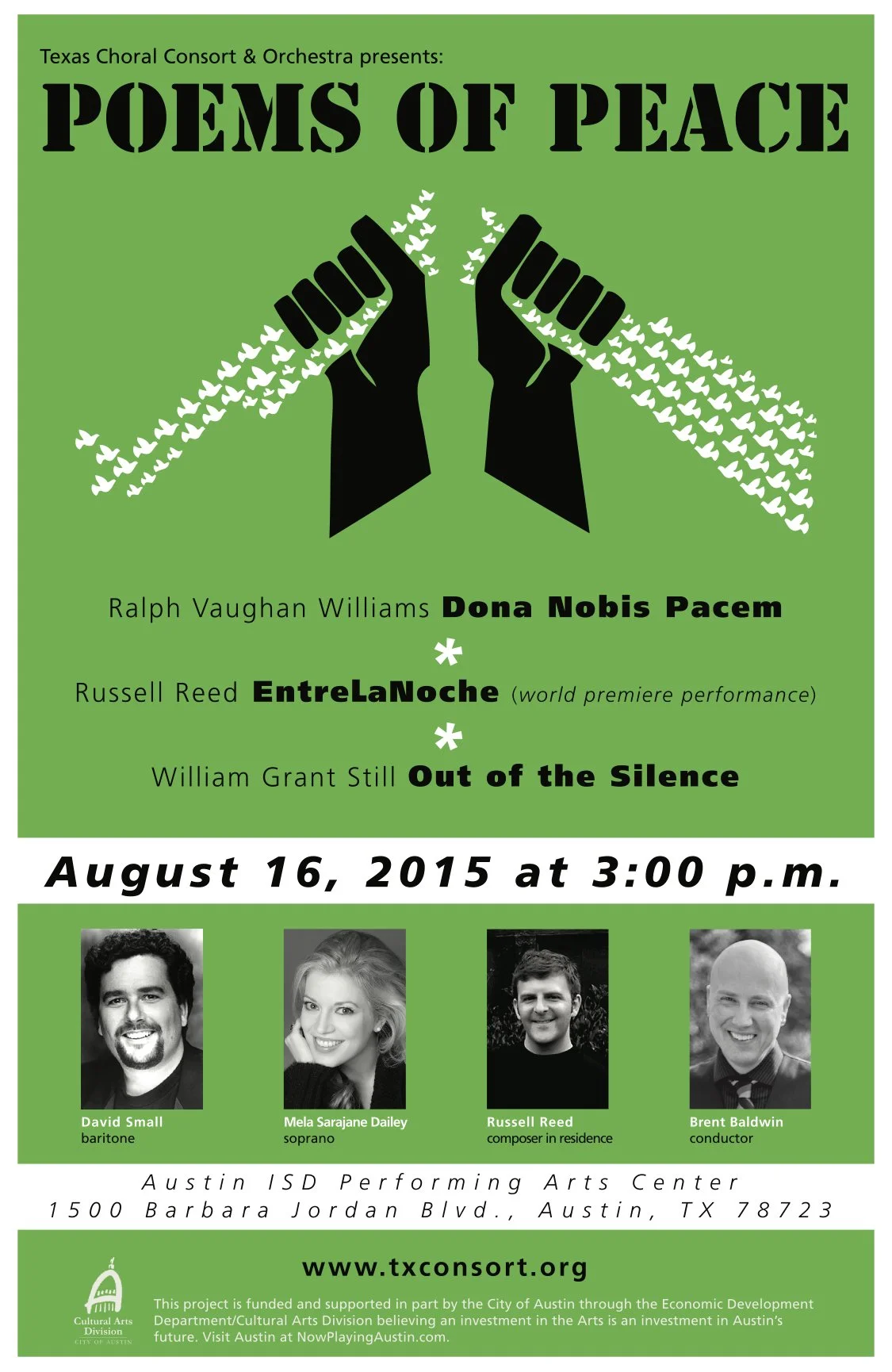

Texas Choral Consort & Orchestra performs Vaughan Williams’ Dona nobis pacem

Poster art by Joshua Ropke

I’d been on another one of my Walt Whitman kicks (yet another artist whose darker side I’d failed to discover as a young person), and it came time to program an orchestral/choral concert for Texas Choral Consort the following summer. I already knew I’d be conducting the world premiere of Russell Reed’s multi-movement, 20-minute EntreLaNoche, and William Grant Still’s Out of the Silence, but I was struggling to come up with the “headliner” work. Because these two two offerings were not widely known (and one had only been heard in un-orchestrated, preview form), I was under some pressure from the TCC board to pick a centerpiece with broad/popular appeal. Something familiar to audiences and musicians alike. Given that we’d just swept the Austin Critics’ Table Awards for a full program of world premiere orchestra/choral works, however, I wanted to go for something a bit more ambitious…

The combination of Whitman and a daily newsfeed filled with mass shootings and international conflict, I was reminded of Vaughan Williams’ epic plea for peace: Dona Nobis Pacem. Decision made, done.

I entered into my score study with the expectation that this work (which I’d heard a bunch, but had neither performed or seen performed) would be another poignant RVW offering, but not much more than that. This was an opportunity to expose my musicians and audience to an important work seldom staged in Central Texas (a huge piece but not a huge “hit”), as well as an opportunity for myself to expand my conducting repertoire while wrestling with it.

I had no idea how deeply I’d come to love the piece. Here there was all of the standard Vaughan Williams aesthetic, but layered with some fierce darkness (Beat Beat Drums) which is underscored by a Whitman text (among others) depicting the horrors the poet witnessed during the American Civil War. The mood swings within the work are at times enough to induce vertigo.

As we rehearsed it throughout the summer, the mass shootings continued (including one in Harris County in our own state, and another in Charleston, SC where my little sister lives) and tears became part of the music-making process for a number of us. In the midst of sadness and feelings of hopelessness, we attempted to live up to that which Leonard Bernstein implored of us years ago: “This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.”

(Well, that plus enacting sensible gun laws, but I’ll not hold my breath for THAT happening anytime soon)

Having had the opportunity to dig so deeply into this work, I’d happily place it alongside Britten’s War Requiem, Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, and the rest of the all-time anti-war masterpieces.

Cheers to Ralph Vaughan Williams, on the 150th anniversary of his birth.

Happy birthday, dear sir. And thank you for helping us make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.

Texas Choral Consort & Orchestra performs Vaughan Williams’ Dona nobis pacem (w/the author on the podium)