Cardew 10 Years Later, or How to Stage a Seven-Hour Epic and Live to Tell About It

One quiet day in 2009, my friend and composer cohort Travis Weller reached out with a query: how would I like to put together a performance of Cornelius Cardew’s The Great Learning with the New Music Co-Op?

I liked Cardew’s music and knew a little about TGL, though I’d had never seen it staged. And for good reason:

Cornelius Cardew (photo: British Music Collection)

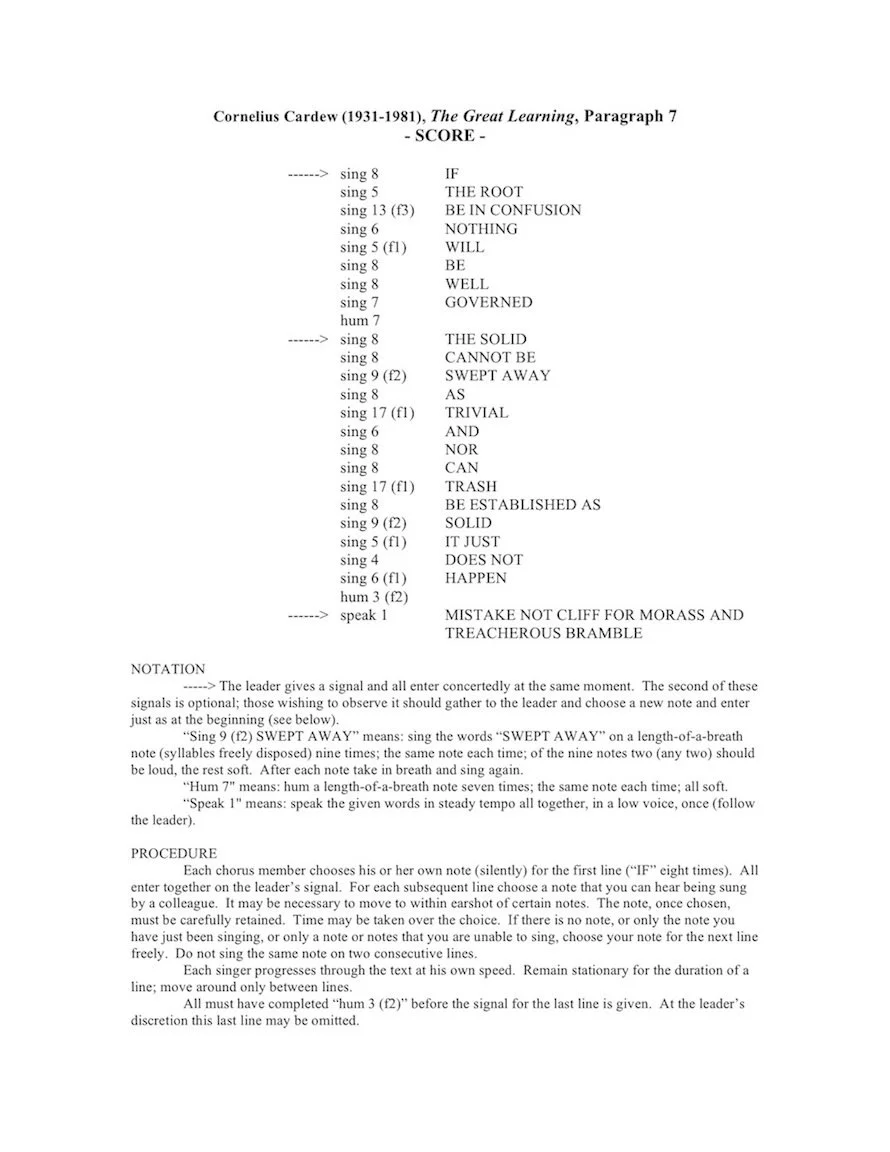

1) The Great Learning score is a lengthy labyrinth comprised of willfully inscrutable directions

2) it’s a seven-hour pastiche of unrelenting sound

3) in spite of it being a forty year-old piece, TGL had never been performed in North America (see also: items #1 and #2)

So sure… I’ll do it. I mean: how hard could it be?

(Spoiler alert: pretty dang hard)

I’d been targeted for recruitment expressly because The Great Learning employs extensive use of chorus, and as a conductor I was fairly well-connected with choral singer community in the Austin (at the time, I was also one of the only such Central Texas conductors who regularly performed new music). I’d recently passed a national audition to become the artistic director of a choral/orchestral group called Texas Choral Consort, and was doing everything I could do to push the ensemble beyond its stodgy masterworks-only past, in part by enlisting composer friends like Graham Reynolds, Russell Reed, Peter Stopschinski, etc. to write new works for it. This happened with substantial pushback from TCC donors, board members, and musicians who preferred the all-dead-white-guys-all-the-time approach, with me surviving more than several attempts to remove me from my post. While the path of least resistance would have been my putting together a pick-up singer group among my contemporary music friends, I REALLY felt that this project represented an excellent opportunity for TCC to shake off its conservative past, and embrace something far more artistically relevant and meaningful.

So sure. I’ll do it. I mean: how hard could it be?

In 2010, Travis and I got together with NMCO members Brandon Young and Sarah Hennies to strategize and conduct feasibility tests on the score. Given that TGL is comprised of seven parts (or seven “Paragraphs” corresponding to the Confucian texts therein), and that each of these movements utilize a different kind of musical force, we came to recognize the possibility of divvying up the portions among our collaborative performing groups (by this time, this also included award-winning Line Upon Line Percussion). We additionally decided to perform the work over the course of two evenings, so as to not burn out our musicians and audience members alike.

Divide and conquer. We had a plan.

Poster by Travis Weller

Fast forward to 2011, and we’re several months out from the North American premiere of this mercurial work. Brandon and I had devoured the score and condensed each movement down to bullet points: information we deemed essential for practical performing parts (we’d cover additional minutiae in rehearsals). The instrumentalists began holding get-togethers for the non-choral Paragraphs 4 and 6 (to which I also contributed banjo and vocal sounds) while I rehearsed the TCC singers (or — more accurately — the smaller subset of members adventurous enough to go along for this bumpy ride). Paragraphs 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 are heavily reliant upon a well-rehearsed chorus, not least of which the a cappella final movement. Each participating vocalist brought much love, energy, and care to the rehearsals, and I was extraordinarily pleased with the TCC singers, as terrified as some of them surely were in taking on such a massive piece. We then converged all forces together in an intense five-day rehearsal process on the lead-up to opening night.

The Great Learning was performed ten years ago on the evenings of May 6th and 7th, 2011, and was very well-received by audience and press alike. I was especially grateful for the favorable press New Music USA showered upon us, though not only for the national-level kudos: as these concerts were such an epic whirlwind, I can still barely piece together my own memories of them. Even in executing the work over two evenings, we were still left with two unique back-to-back concerts, each lasting more than three hours. With pure adrenaline and devil-may-care bravado, however, we powered our way through the maelstrom together, and I’m thankful there exists documentation to make up for my own sketchy recall.

A messy cover page serving as prelude to a FAR messier score…

But there is one highly distinct event I’ll never forget…

Austin’s Pecan Street Festival coincided with our concerts, and was buzzing with activity but a few blocks from our venue. We were in the middle of our quietest portion: the dense-but-delicate Paragraph Seven which serves as the a cappella finale of the entire work. Out of nowhere wafts the distant sound of…

No… it CAN’T be…

The distinctly non-dulcet tones of bagpipes…

You MUST be kidding me.

My first internal reaction: “oh come ON… all this work and for so long, only to have it dashed in the seventh hour of music by a damned bagpipe player?”

(I’ll spare you the actual unedited, Rated-R content of my mental monolog)

Cardew’s score for Paragraph Seven

But as the seemingly endless minutes passed and the internal "oh god will you just PLEASE STOP” mantra subsided, I became aware of something: my ears began to dig more deeply into the persistent reedy sound, and I started to hear how this new sonority interwove itself within the choral fabric in a most brilliant way. Even though were were exploring atonal territories, the sounding mode produced by our bagpipe player friend — in its own wondrous way — meshed beautifully with what we were singing. Given the aleatoric nature of the music, we were able to make gradual, microtonal adjustments as a collective and, in effect, absorb our surprise musical guest into the sonic tapestry.

In speaking afterwards to ensemble members, it turns out each one of us experienced the identical “OH NO… oh damn… oh wait… oh WOW” inner process as I did. We ended up reprising Paragraph Seven on the New Music Co-op Ten Year Anniversary concert, and more than several participants lamented the absence of bagpipe. While Cardew has been in his grave for decades, I surmise that — were he to have experienced that moment with us — he might have embraced its beauty and sought not to change a thing. In my long artistic career, this unforgettable and irreproducible moment remains a musical highlight of my life.

And to all my Cardew colleagues near and far, Happy 10th TGL Anniversary!